Smarties in letters from ‘Amme’ in London

By Farkhanda Muneer

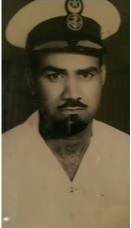

My father Khurshid Ahmed came to the UK as a naval attaché at the Pakistan embassy in London in 1964. It was a coveted post, and Khurshid had been selected from among hundreds of officers after undergoing medical, English and proficiency tests. Accompanying him was my mother, Naseem, and their three young children. Living in London and working at the embassy was an amazing experience for Khurshid. He had been deeply affected by his upbringing in a small village in Pakistan. His father, a schoolmaster, had encouraged all his sons to study and get a profession. Khurshid had joined the Pakistan Navy and excelled, becoming an officer and winning trophies as part of its Kabbadi team. But his sisters had married young with little education. Khurshid wanted his children, particularly his daughters, to have a better quality of life and better opportunities. It wasn’t long before Khurshid and Naseem started making plans for a future in the UK for their growing family (I and my sister were born soon after they arrived).

Khurshid had by now served 20 years in the Pakistan Navy and was due for discharge with a full military pension. Gaining citizenship in the UK was possible due to how long the couple had been residents, with two of their children born in London. However, Pakistan was in a fragile political state at the time, and this was to have far reaching effects on their plans to settle in the UK.

Pakistan was ruled by the unpopular military dictator General Ayub Khan, and on a state visit to London in 1966, he faced protest from Pakistanis living in the UK. My father told me how angry General Ayub had been on his visit to the embassy, complaining that he had paid for these students to come and study in the UK only to be humiliated by their protests. This was the start of a crackdown on Pakistanis coming over to the UK for study or work, and ultimately led to a recall of some expatriate workers and students, including my father. Coupled with this were the India-Pakistan wars of 1965 and 1971, for which the Pakistan Navy recalled all personnel. Khurshid’s request for discharge was denied and he was recalled to Pakistan.

This left him in a difficult position, as he wanted his family to have a future in the UK. My parents made the painful decision to split the family, with Khurshid returning to the naval base in Karachi with the two youngest children (aged 2 and 3), leaving Naseem with the older kids, who were by then in primary school. Before he left for Pakistan, Khurshid bought a house. The plan was for him to send money from Karachi and for Naseem to look for a job locally to support the family. My father left for Pakistan to try and secure his release from the navy, but not really knowing when he would return. Back in London, Naseem missed her two youngest children and her husband, but struggled on. The small local Pakistani community was very supportive. She found two jobs to keep the family going. She was very social and loved mixing with friends from different communities, chatting to people on the buses or in the local shops. Even now her friends recall her kindness and funny jokes. It was an exhausting time for Naseem and she often came home and collapsed on the bed. This was in the early 1970s when the National Front and Enoch Powell were inciting racism, but Naseem’s friendly personality helped her through adversity.

Neighbours threw eggs at her and the children, but years later the same neighbours became our friends. Once people got to know their Pakistani neighbours and their children became school friends, the racism reduced.

Meanwhile in Karachi, my father too struggled with two young children who desperately missed their mother and siblings. He appealed for help from his family and his older sister Fatima came to support him, becoming a surrogate mum to the two toddlers. We never forgot our mum in England and every plane that flew overhead we’d ask our dad whether ‘ammee’ was on it. He would always say yes, she was coming, which reassured us, along with the letters mum sent us with Smarties inside. We became more comfortable in Karachi, loving the freedom of playing with local friends all day in hot weather.

Despite my father’s repeated requests for a discharge, the navy refused, and the months turned into a year, then approaching two years. Frustrated and concerned he may never be able to return, he changed tack and went to see his commander’s wife with his two little daughters, making sure the commander was out at the time. It was a desperate plan and one that could have backfired. He appealed to the commander’s wife and daughter, explaining the plight he was in with his family separated. It also helped that his two adorable daughters cried at the right moment, helped by my father pinching our legs.The strategy was a success and the commander had no choice when faced with emotional pressure from his family but to release Khurshid from the navy with a full pension.

Within weeks, we returned to the UK to a joyful reunion with the family after a gap of two years. For us, it was a surreal moment, as we had spent most of our lives in Pakistan by then. We had not forgotten our mum, but had forgotten our English and the cold weather. Even worse for me was that on Monday, I had to start at school with no English, whilst my younger sister could stay at home with mum.

Throughout his life, my father maintained a keen interest in current affairs in Pakistan and these were often debated in our house as we grew up. My parents often spoke of their early life and journey to London, thanking god for all the blessings they had received. They both wanted their children to study and have better lives. They instilled in us a strong work ethic and Islamic values that we have in turn passed on to our children.

My father died in 2014 and my mother in 2010, but their legacy lives on in their children and grandchildren, who have gone on to work and study in the fields of law, medicine, engineering, finance and management. We tell our children about the sacrifices their grandparents made and the vision they had for future generations, how proud they were of their family and how they now share the responsibility to carry on their legacy by embracing all the opportunities this country has to offer.

Spotlight On Haris Jawaid

This episode of Outstanding British Pakistanis features the remarkable

Award-winning writer Ishy Din leads brand new BPF Writers’ Lab for aspiring writers

Soho Theatre Walthamstow and British Pakistan Foundation have launched